What was once a petty theft has today, been blown into a full-fledged enterprise-level attack. The history of ransomware is interesting and organizations can prepare themselves better to understand how impactful the attacks have been in the past. Every enterprise needs to be concerned with cybersecurity and avoid a ransomware attack at all costs.

Ransomware groups were successful in growing their targets by 55.5% by 2023, reaching a total of 5,070—a significant rise from 2022. The second and third quarters alone saw 2,903 victims, surpassing the total for all of 2022. The leading ransomware groups continued to be the veterans: LockBit3.0, ALPHV, and Cl0p.

The idea of taking someone or something valuable hostage in return for a ransom itself is quite old and has led to some “impossible missions” in Hollywood movies as well. And when it’s a computer or a network or an asset of a company connected to the internet, it becomes a ransomware attack. The earliest documented ransomware attack dates back to 1989 in a case where the AIDS trojan (PC Cyborg Virus) was released via floppy disk. Victims of this attack were required to transfer $189 to a P.O. box in Panama if they wanted to access back their systems.

Now, for a very long time, up until the 2000s, ransomware attacks remained rare and one-off not because they were difficult to conduct, nay, rather the collection of ransom was a challenge. Then with the advent of virtual currency(2010), collecting payment without leaving a trace ignited ransomware back to action – remember the screen-locking virus?

Bitcoin – an instrument of the threat actors

Bitcoin was a game-changer for cybercriminals. It provided a frictionless payment method, allowing them to operate globally with minimal risk of getting caught. However, the digital divide reared its head. Not everyone is crypto-savvy. Many victims were unfamiliar with Bitcoin, creating a roadblock in the ransomware business model. To overcome this, some cybercrime syndicates have gone as far as establishing call centers to walk victims through the Bitcoin purchasing process. It’s a bizarre twist on customer service – helping people pay to regain access to their data. Essentially, they’ve turned ransomware into a more sophisticated business model, complete with “customer support.”

Cryptolockers – a new breed of ransomware

Cryptolockers are malware that can damage any data-driven organization. 2013 was a ripe time for the introduction of Cryptolockers – a new breed of ransomware that harnessed the power of Bitcoin transactions and combined it with enhanced forms of encryption. The application when executed encrypts the files on the desktops and network shares and hijacks it. Anyone who tries to open the file is prompted with a message of paying a fee to decrypt it. It used 2048-bit RSA key pairs generated from a command-and-control server to enter a protected network of emails, file-sharing sites, and downloads. Back in the day, it demanded a ransom of around $300 for the key.

Cryptolockers used Trojans for the delivery of extortion. The potential value of ransomware with strong encryption was first realized by the threat actors behind the botnet.

Ransomware – an organized business

the masterminds behind botnets soon realized that ransomware was a much more lucrative business than their previous methods. Instead of stealing small amounts of money from individual bank accounts, they could hack entire computer systems, hold them hostage, and demand large sums of money to unlock them. CryptoLocker was a turning point in a way that it sparked a wave of copycat attacks, similar to a gold rush where everyone wanted to get rich quickly by finding gold. This period marked the beginning of ransomware as a major cybercrime problem.

It took the FBI and Crowdstrike researchers to shut down the operations of the Cryptolocker Gameover Zeus. This was the true inflection point of the ransomware’s growth. Security researchers were successful in finding Cryptolocker clones in the wild with criminals tracing back to all over the world. Cybercrime became more popular due to its organised and corporate nature and many new criminals started to take interest.

Ransomware takes the media

To stand out from the crowd, more serious players pivoted to a new style called BGH which stood for Big Game Hunting. It is a technique that combines ransomware with the tactics, techniques, and procedures that are common to the attacks made for larger organizations. This is like the ABM of cybercrime where you focus only on a few key accounts worth a high value that can justify the time and effort. The CrowdStrike® 2020 Global Threat Report recognized BGH as one of the most prominent threats in 2020. This trend continued into 2021, a high-profile example being that of a US fuel pipeline.

Increasing pressure by the Ransomware actors

Various techniques were applied by cyber attackers to force extortion out of their victims. One of the problematic emerging threats was to not only hold data hostage but also suggest releasing it online to the entire world. This meant the pressure was now double to save the data as well as to stop it from falling into the hands of competitors or other cyber criminals. Not only that, the threat actors are more dramatic. They exfiltrate the data slowly and gradually starting from the least damaging ones and moving to the most – movie style. This meant that the pressure slowly mounded over the company whose data had been held hostage.

It was observed by Crowdstrike that the actors increase pressure with credible threats of distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks upon non-receipt of ransom. The company also observed that eCrime adversaries collaborated and even shared their tactics.

How will Ransomware evolve?

Cybercriminals engaging in BGH ransomware have rapidly evolved when it comes to techniques and the cautions followed during implementation. This trend is expected to continue at a pace and it’s up to the organisations to have a strong cybercrime mechanism ready with them.

A brief history of ransomware attacks

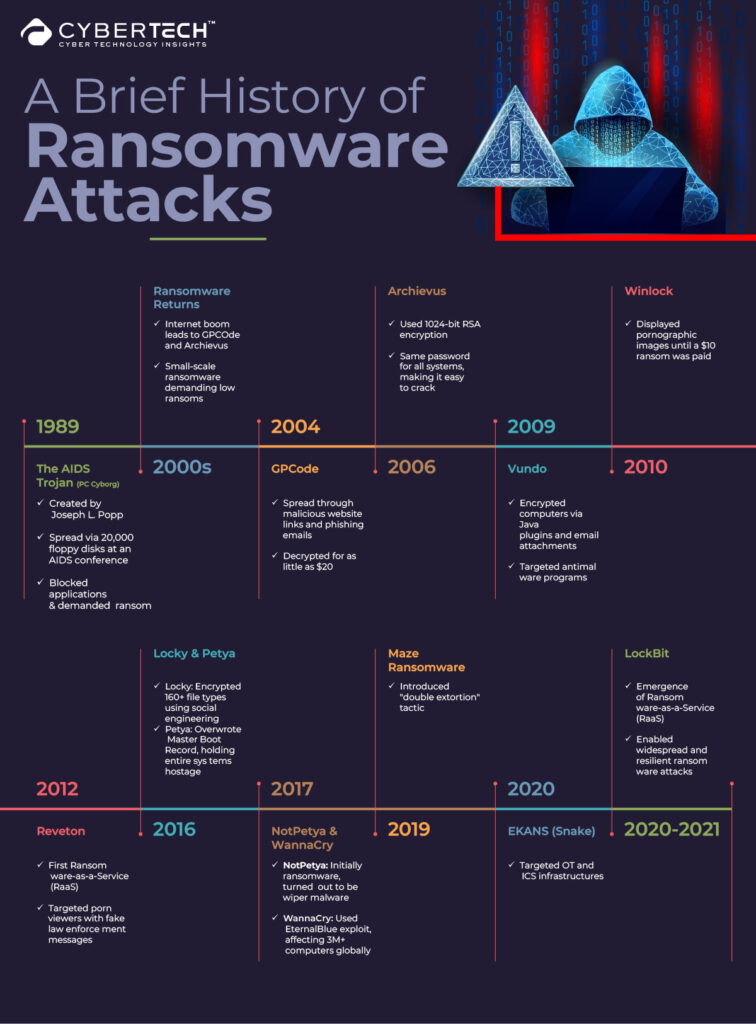

1989 – The AIDS Trojan (also known as PC Cyborg)

WHO held an AIDS conference in 1989, following which, Joseph L. Popp, a Harvard graduate biologist, created and mailed 20 thousand floppy disks to those who attended the event. According to the packaging the disk contained a questionnaire determining the chances of someone getting infected(with AIDS).

Back then, ransomware was unheard of, and the attendees executed the floppy disk in good faith only to find out that the “AIDS Trojan” had infected their system and blocked all applications.

2000s: Ransomware returns as the internet booms

With the rising popularity of the internet and emails being sent to and fro, threat actors saw an opportunity. This led to the creation of GPCOde and Archievus – petty ransomware that bulk targeted and asked for less ransom.

- 2004: GPCode used malicious website links and phishing emails to infect a system. The encrypted files were decrypted for a ransom of as little as $20. Many victims were able to crack the encryption key on their own.

- 2006: Archievus was a bit stronger. It used the 1024-bit RSA encryption code. However, the authors of Archievus used the same passwords for all systems which made it easy for victims to crack the code.

2009: Vundo

The Vundo was a virus that encrypted computers using the shortcomings of the browser plugins programmed using Java or entered systems through email attachments. Vundo attacked or suppressed antimalware programs such as Windows Defender and Malwarebytes.

2010: Winlock

Ten threat actors from Moscow hijacked a system to display pornographic images until a ransom of $10 in rubles was paid.

2012: Reveton

Reveton – the first ransomware as a service (RaaS) on the dark web, provided a paid and organized way for cybercriminals to commit attacks. This was especially targeted towards porn viewers. It displayed fraud messages of law enforcement to threaten jail time if the victims did not pay the ransom.

2016 – Locky, Petya

Locky could encrypt more than 160 file types and was spread using fake emails with infected attachments. It was spread using social engineering. Petya deviated from the then-standard practice of encrypting individual files. Instead, it targeted the entire disk volume by overwriting the Master Boot Record (MBR) to prevent the operating system from booting until a ransom was paid, effectively holding the entire system hostage.

2017 – NotPetya (Ukraine and Wiper Malware) & WannaCry

NotPetya started as a ransomware but was later found to be a wiper – a virus that causes disruption. The ransom part existed but the data was already damaged. Another one, WannaCry, used the EternalBlue exploit, developed by the NSA. It affected more than 3 Million computers across 150 countries until it was finally disabled with a kill switch.

2019 – Maze Ransomware

This introduced the concept of “double extortion,” where attackers encrypted the files and also threatened to publish stolen data unless a ransom was paid.

2020 – EKANS (Snake) Ransomware

The first ransomware was dedicated primarily to targeting OT (operational technology) and ICS (Industrial Control System) infrastructures.

2020-2021 – LockBit – Emergence of Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS)

RaaS platforms created a business model out of ransomware by renting out the infrastructure and the tools to untrained threat actors required to conduct a cyberattack. This made it easy for anyone without a background to jump into this business.

Conclusion

Looking back at the history of ransomware, we can see how it has evolved into a dynamic landscape. Cybercriminals have continuously adapted their tactics to maximize their illicit gains. From the early days of ransomware attacks to the sophisticated, enterprise-level attacks of today, it has grown into a formidable challenge for organizations worldwide. As ransomware techniques become more advanced, businesses must stay vigilant and proactive in their cybersecurity measures.